Velocity enhancement programs have become significantly more mainstream over the past few years, and with them so have “arm care” programs. While many arm care programs are well intentioned, they often fail to meet the goal of keeping throwers healthy and on the road to improvement.

Forces Acting on the Shoulder

Throwing is a complex movement pattern that places significant demands on a variety of structures in the body, especially the throwing arm. Throwing is the fastest movement in sports, with the shoulder reaching peak angular velocities of 7,250 degrees/second (Wilk et al., 2009). Anterior translation forces (humeral head moving forward on the glenoid fossa) are also estimated to be equal to one half bodyweight during the late cocking phase. Additionally, distraction forces (humeral head being pulled away from the glenoid fossa) are estimated to be equal to bodyweight during the deceleration phase (Wilk et al., 2009).

Shoulder Anatomy

So, what does all of this mean and how does this affect you and your arm care routine?

It means that the extreme range of motion needed to throw at high velocities requires enough laxity to allow these movements, but also enough stability to prevent injuries and pain.

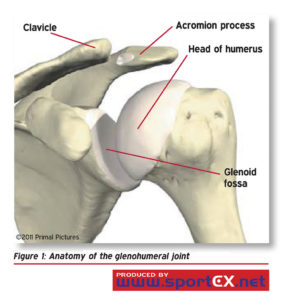

The joint that most people think about when referring to the shoulder is the glenohumeral (GH) joint. This is where the head of the humerus sits in a shallow socket of the scapula, known as the glenoid fossa, but there are actually four joints that make up the shoulder. All of these joints must work together to safely allow movement. If any joints of the shoulder become dysfunctional, movement will be restricted, compensations will occur, and injury becomes more likely.

For example if the scapula (part of the scapulothoracic joint) starts from a more depressed position, it will be difficult to get to a good upwardly rotated position, which is necessary to get the arm overhead. This is one reason assessments are so important; we need to know an athlete’s weak points so we can address them and make sure we aren’t prescribing movements that will make the problem worse.

Another important piece of the shoulder is the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is made up of four muscles that originate on the scapula and attach on the humerus, to help stabilize the ball on the socket and keep the shoulder from dislocating. These muscles have an important job and become fatigued due to the acceleration and deceleration of the arm during the throwing motion.

When all of these forces are acting on the shoulder during the throwing motion, the muscles of the rotator cuff are working to keep the head of the humerus on the glenoid fossa. For example, while the arm is being accelerated, the pec and lat are helping with a lot of the gross movement, but the subscapularis is working to make sure the humeral head doesn’t come off of the glenoid fossa.

Arm care programs tend to focus on movements for the rotator cuff, which are necessary to keep athletes on the field, but misguided in their prescription post-throwing.

What Arm Care Should Not Be

Arm care is a great concept, but tends to end up including too much volume of rotator cuff work. After throwing, the muscles of the rotator cuff are fatigued from accelerating and decelerating the arm, as well as ensuring the arm stays attached to the body and does not dislocate.

When a high volume of rotator cuff work is prescribed post-throwing, it tends to result in poor arthrokinematics, or small movements at joint surfaces. This means these movements may go unnoticed until they’ve caused damage and led to poor movement patterns. For example, the head of the humerus may glide forward in the anterior capsule, rather than staying centered during internal or external rotation, causing eventual pain and lack of stability in the front of the shoulder.

Also, arm care should not include distance running or poles. Steady state aerobic activity does not help improve the necessary capabilities of pitchers; it just gets athletes moving slowly and adds more fatigue and stress. This has been covered in depth by a lot of other coaches, but if you’d like some options instead of distance running, check out this article.

What Arm Care Should Be

Arm care is meant to be an opportunity to speed the recovery process and work on athletes’ specific stability and mobility needs to improve performance and health.

Moderate intensity exercise has been shown to reduce muscle soreness and improve some performance metrics (Tufano et al., 2012). Doing some light movements involving the upper extremity may help move the inflammatory process along and get you back to feeling better, sooner.

Arm care programs also offer an opportunity to work on weak points that are holding you back from moving and feeling your best. This is the time to do some reaching movements to help counteract your depressed scapulae, improve your thoracic rotation, or hip internal rotation. Some mobility exercises can be extremely demanding, and the post-throwing period offers an excellent time to consolidate stress by performing them then.

Below is a side-lying T, which is a good option for improving thoracic rotation with the assistance of gravity.

The final piece of an arm care program can be myofascial release. A study by Pearcey et al., found that myofascial release after intense exercise improved the recovery of muscular performance, with the intervention group showing greater power speed, and change of direction (Pearcey et al., 2015).

While arm care is typically thought of as a post-throwing activity, it should also be applied to throwing preparation. Getting your body prepared to throw and activating necessary muscles is extremely important for maintaining health and performing at a high level.

Arm care isn’t a cure-all; it’s one piece of a well-rounded training program. Like all other parts of the training program, make sure it’s well thought out so it serves the desired purpose.

Resources

Photo:

“Anatomy of the glenohumeral joint” by sportEX journals CC BY-ND 2.0

Wilk K, Obma P, Simpson C, Cain EL, Dugas J, Andrews J (2009). Shoulder Injuries in the Overhead Athlete. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy.

Tufano JJ, Brown LE, Coburn JW, Tsang KK, Cazas VL, Laporta JW (2012). Effect of Aerobic Recovery Intensity on Delayed-Onset Muscle Sorness and Strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Pearcey GE, Bradbury-Squires DJ, Kawamoto JE, Drinkwater EJ, Behm DG, Button DC (2015) Foam Rolling for Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness and Recovery of Dynamic Performance Measures. Journal of Athletic Training.