Despite what the internet and some coaches may lead you to believe, there is more than one approach to high level pitching mechanics. While the hip hinge and “sitting into the back leg” gets a lot of attention, it is not the only way to throw hard, and it is not the best approach for all athletes.

Type 1 vs Type 2 Back Leg Mechanics

The concept of matching mechanics to athlete type has been around for a while, but some prominent coaches such as Steffan Jones and Stuart McMillan have some interesting ideas about classifying and training these athletes. While the baseball throwing mechanics are a bit different I believe this concept can be applied to pitching as well.

Type 2 back leg mechanics involve a more vertical shin and greater depth of the back leg (think deeper box squat). They also tend to involve more of a hip hinge and some forward flexion of the torso.

Type 2 back leg mechanics involve a more positive shin angle (knee forward of ankle), less depth on the back leg, and a more upright torso (more like a shallow front squat).

| Type 1 | Type 2 | |

| Shin Angle | Vertical or Neutral | Positive angle |

| Depth of Back Leg | Deep | Shallow |

| Torso | Forward flexion with hip hinge | Upright |

Neither of these mechanical approaches are superior in a general sense. The key is to identify athletes who are using an “authentic” movement solution as Stuart McMillan would say, vs athletes who are moving inefficiently due to restrictions or poor coaching.

Athletes should be allowed to move like individuals rather than robots, but not all athletes will self-organize to an efficient pattern. While throwing is a foundational skill that children learn as they develop gross motor skills, pitching is a bit more complex and often requires more in-depth training and coaching. Some athletes may have strength, movement, or mobility limitations that they must overcome, or they may just need a bit more specific training.

Benefits of Each Movement Pattern

Type 1

In order to produce muscle force, most type 1 pitchers take advantage of the slow stretch shortening cycle (slow SSC). The SSC is the rapid stretch of a muscle (eccentric or lengthening muscle action) followed immediately by the shortening of a muscle (concentric muscle action).

The SSC can be further divided into fast and short stretch shortening cycles. The fast SSC occurs in <250 milliseconds, whereas the slow SSC occurs in >250 milliseconds. The tendon is the primary site of the storage of elastic energy as it cannot be volitionally contracted, therefore the tendon will try to stay at its same level of tension. This means that in order for the tendon to store and release elastic energy effectively the muscle must be “pre-activated” or “pre-stretched.” So, the muscle is less compliant during the eccentric and isometric phases forcing a larger stretch to be placed on the tendon, generally leading to a more powerful rebound (myotatic or stretch reflex). The stretch reflex senses a change in length in the muscle-tendon complex and responds with a muscle contraction in order to avoid injury. However, if the stretch is too great, the force will be reduced due to activation of the golgi tendon organs (a sensory receptor organ that senses change in muscle tension).

An easier way to think of this may be that the slow SSC is like a thick rubber band-a lot of potential energy, but it takes more effort to load it and you can’t load it very fast. Whereas, the fast SSC is more like a rubber ball-loading it fast results in more energy.

The pre-stretch of the muscle has been shown to improve the performance of the concentric muscle action provided that the time between the two contractions is minimal (Cavagna, 1977). Basically, if you can sync up the myotatic reflex with the concentric action there is a double bounce effect.

A type 1 back leg approach allows athletes more time to form cross bridges and develop muscle force. The greater range of motion and increased time before foot strike allows type 1 pitchers to produce more muscle force as they aren’t as great at storing and releasing elastic energy. This approach can also make upper body counter rotation a bit easier and help set up athletes, who are not hypermobile, with the ability to create hip/shoulder separation.

Along with the use of slow SSC type 1 pitchers also tend to use a slower rate of loading. Meaning they “drop” into their back lack a bit slower than their type 2 counterparts. If force dominant athletes attempt to use a type 2 style they do not have time to fully express force, and are likely to see diminished throwing velocity.

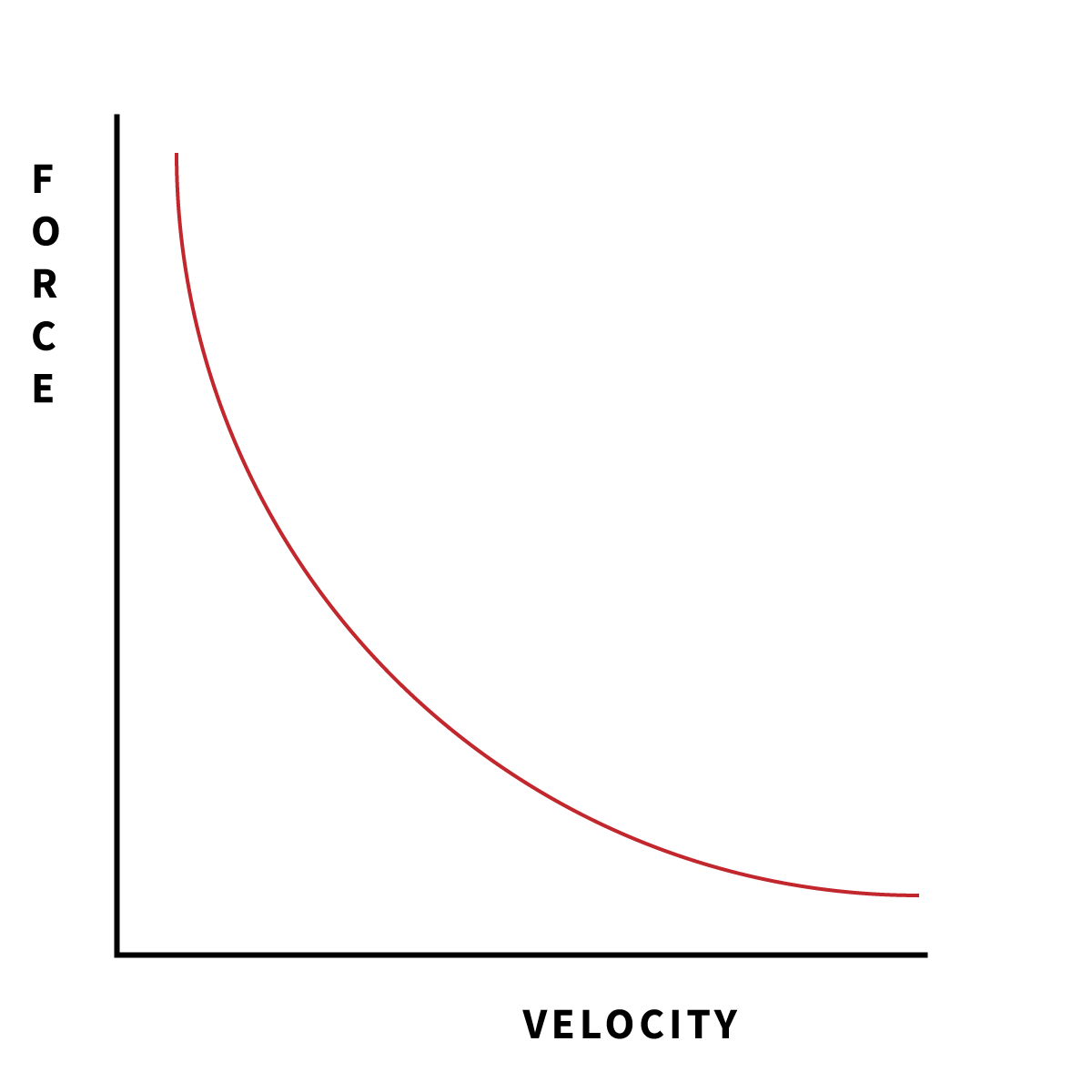

Therefore, athletes who profile more on the force end of the force-velocity curve may benefit from this approach as it plays to their strength (pun intended). In part 2 of this article series I’ll help you determine if this applies to you.

Type 2

A type 2 back leg approach tends to result in less counter rotation of the upper body. However, athletes who efficiently use this approach still have significant hip/shoulder separation often due to their relatively superior mobility. Since these athletes store and release elastic energy more efficiently, they do not need to go through the same range of motion that muscle driven athletes need to in order to produce high velocity.

The type 2 approach uses the fast SSC and relies on the storage and release of elastic energy to a larger degree than the muscle force employed by a type 1 approach. You’ll generally notice a faster rate of loading as well.

Athletes who use this approach tend to fall farther to the velocity end of the force-velocity curve and this approach tends to play to their strength.

Conclusion

Neither back leg approach is superior in a general sense. Each strategy must be matched with the appropriate athlete to achieve peak performance. Stay tuned for Part 2 of this article series where we will discuss the necessary underlying physical capacities for each approach and training considerations.

Interested in training in person or remotely with Tyler Anzmann Performance? Send me an email and let’s discuss your needs and goals.

Resources

Cavagna G (1977) Storage and Utilization of Elastic Energy in Skeletal Muscle. Exercise and Sports Sciences Reviews.

“Daniel Espino Prospect Video, RHP, Georgia Premier Academy Class of 2019, CF.” Shortened to three seconds and made into a still image. By Prospect Pipeline. Licensed by CC BY 2.0

“Diaz vs Balentien-Puerto Rico vs Netherlands 3/20/2017 (via @TheDonGiggity).” Made into a GIF and a still image. By Luis Garcia. Licensed by CC BY 2.0